Written by: Margaret López / Venezuela

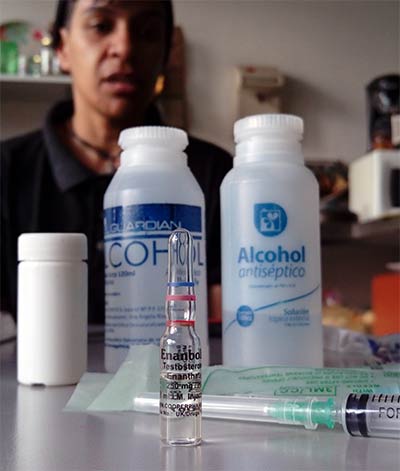

Caracas. There are five disposable syringes, an empty alcohol bottle, and a small container full of cotton on the table. The main protagonists are the 250 mg Enanthate vial, which is an injectable testosterone, and Denangel Meza, a 38-year-old transgender man.

“I waited for this vial for five years. I left university and I was still waiting for the vial. Until, finally, I was able to get it and inject myself today,” says Denangel Meza, minutes after administering his body with its first extra testosterone dose.

The growth of facial and body hair, the increased strength and muscle mass, and of course, a deeper voice, will be some of the effects that will show after initiating a masculinizing hormone therapy. A treatment that, for many other transgender men in Venezuela, is a luxury that they cannot afford and that no public hospital or clinic provides for free, in contrast with countries such as Mexico and Costa Rica.

Testosterone administration does not take place in a medical center or anything of the kind. Denangel Meza broke the vial he dreamed about since his university days and administered it in the kitchen area of an office in Caracas. It was in the sofa, within that same space, where he took a solid step towards his transition from a female body to a male body.

However, Denangel Meza is lucky. He administered the first dosage that will spark a chemical alteration in his body with the support of a nurse, who has been his friend since childhood, Joseph Soto, and Julián Alejandro Ulloa, two of his accomplices at Transgresores (Transgressors), a Venezuelan group of trans men.

He studied to become a customs broker but that wasn’t enough to obtain the USD $50 that it cost to buy 10 testosterone doses in a bodybuilding store in Caracas. He had to set up a business and sell several products to obtain the money that equals two years of work in Venezuela, if you consider how little an employee who earns the minimum wage, calculated in the official exchange rate, makes. He also had emotional support and shared his experience with his circle of transgender friends, but there were no doctors by his side.

Since 2009, international protocols for these types of hormonal therapies set by the U.S. Endocrine Society establish that hormone therapy should only start after blood tests, a lipid profile, sugar levels in blood, and a measurement of liver enzymes, besides a physical examination, to set a monitoring center to supervise the appearance of the body and the size of female genitals such as the clitoris, as well as the mammary glands.

According to scientific studies, after three months of testosterone injections, transgender men usually experiment the interruption of the menstrual cycle, enlargement of the clitoris, and a change in vaginal hydration, as well as acne, weight gain, and hair loss, which are considered as side effects of the increase of testosterone levels in a female body.

That morning, Denangel Meza didn’t have to sign a medical consent form to acknowledge the changes and risks that come with the hormonal treatment. Although everyone congratulated him, no one asked about blood tests or who was the endocrinologist who would monitor his masculinizing therapy, which requires testosterone injections every 28 days; nevertheless, everyone in the room knows the answer: The Internet will provide medical support.

They have tried. The three transgender men coincided in visits to the doctor at the Family Planning Civil Association (Plafam) and in Reflejos de Venezuela (Venezuela Reflects), an NGO that fights for the rights of the LGBTQIA community, as well as in a private medical center that had a forerunner unit in Venezuela that provided medical attention to transgender women in the 80s and 90s.

“What bothers me is that I had to prove I was transgender. It wasn’t enough for me to go to a medical center and say, in front of the personnel, that I want to start a chemical gender transition process. Is that really not enough? I am coming to you with gender performance, to tell you that my name is Joseph, and I enunciate myself as a male. This exercise alone requires too much courage,” says Joseph Soto, a 27-year-old transgender man, who cannot help raising his voice when he remembers his quest to find an endocrinologist in Caracas.

Before he could have access to an introduction about testosterone and its effects, he was forced to attend several psychiatric consultations. Then they asked him to bring two people, one family member and one work colleague, who could verify that Joseph Soto acted as a man in his everyday life. Without passing this test, he could not receive the hormonal treatment he needed to complete his transition.

Joseph Soto’s case is proof of the lack of protocols for the medical attention of transgender people in Venezuela, in contrast with the existing ones in Argentina and Uruguay. These documents are key to facilitate inclusion and, at the same time, lower the stigmatization levels in regards to a condition that was considered as a mental illness until 2018.

Last year, transsexuality was no longer considered as a pathology in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, also known as DSM-5, a manual edited by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), which is used by psychiatrists all over the world.

This was achieved by Stop Trans Pathologization, a group that launched a campaign to depathologize gender transition. Nevertheless, this victory is quite different from when homosexuality stopped being considered as a mental illness by the APA in 1973 and by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1990.

The most important difference is that transsexualism, as few other conditions, requires the active participation of doctors, who will guide the patient through the transition process. As sociologist Beatriz Cavia explained in her article “The Management of the pathological: The Itineraries of Trans-sexuality,” there is a singularity about trans people “in regards to the medical requirements needed to manage the different possibilities of transformation for the body. The need for medicine for transitional health is indicated as well as the signification of the variations of gender during childhood and adolescence.”

Nevertheless, an appointment with mental illness experts seems to be fixated as the main meeting point with the trans community. “We know that the expectation is neither to see a psychologist nor a psychiatrist. Our intention is to accompany them because we know that trans people might have some psychological vulnerabilities as a result of prejudice, rejection, and the harassment they have experienced and that could have negative connotations,” says Gilberto Aldana, psychologist and director of the José María Vargas hospital.

Aldana is one of the seven contributors at Unitrans, a pilot unit that hopes to become a new model. This service started to take shape in October 2018 and now it offers a network comprised by psychology, psychiatry, endocrinology, plastic surgery, urology, and social work to provide public, specialized healthcare services for the trans community.

This public service officially launched on August 19 and provides services for at least four patients every day. The operation of Unitrans has been approved by the technical committee of this public hospital in Caracas and was assigned a physical space in Room 20, where the urology department is located, but it is far from receiving a budget by the Health Ministry.

Urologist José Gregorio Álvarez was the one who promoted Unitrans. Its financial plan consists in the creation of a foundation that has not been registered but which aims to obtain funds from the Venezuelan government, as well as from other international organizations focused on helping the trans community.

“The aim is not only to treat national patients, but also the international patients who need it. Another goal is to turn this into an educational institution for other doctors,” says Álvarez, who acknowledges that attracting other trans patients who are interested in sex reassignment surgery can turn into an income source for this project in the medium-term.

Unitrans Foundation estimated the cost of a vaginoplasty at USD $8,000, which is a surgery with the purpose of constructing a vagina. This price involves a competitive factor if you consider that in Colombia, this same surgery is priced at USD $15,000, whereas in the U.S., the price exceeds USD $30,000.

The visit of urologist Maurice García to Caracas is an important part of the costs considered in this initial budget, since Álvarez has only participated as an assistant in a few vaginoplasties. García is the director of the Health and Surgery Program for Transgender People at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, which was founded in 2017. There, García has been in charge of over 1,000 sex reassignment surgeries.

Nevertheless, this surgery is not as popular as before. Now, many trans people question the extent to which they should fit their bodies into the canonical and traditional model that dictates how a woman or man should look like and they opt for minor esthetic changes nowadays.

“The sequence of surgeries was quite dogmatic before and we are open. Surgeries will take place according to the needs of each patient, whether it is a mammoplasty, facial feminization, or body contouring. We will work with urology only when performing vaginoplasties,” says Juan Blanco, the head of the Plastic Surgery unit at the José María Vargas hospital.

Whether they want a sex reassignment surgery or not, it will be a personal decision but everyone will have a medical history with two different names: the one they choose according to their gender identity and the one that was given to them when they were born. Since it is a public hospital, it is compelled to fulfill these requirements because there is not a legislation that guarantees their name change in Venezuela.

The global movement launched by Stop Trans Pathologization is fighting so that legal name changes for trans people are made official without asking them for medical and psychiatric reports. This requires the improvement of the old 90s doctrines, which required sex reassignment surgery as an essential requisite for an official name change, so that the sex was consistent with the person's gender identity.

“Venezuela was the first country in the region to recognize the identity of trans people in 1977 and later, there was a sentence (of the former Supreme Court) in 1982, issued by Alirio Abreu Burelli. Since then, there were around 150 gender identity recognitions, basically, through the rectification of birth certificates, amparos, and material errors. There were several legal formulas available until 1998 and everything stopped there,” lawyer Tamara Adrián remembers.

Adrián is a law professor, she is the first trans lawmaker in the National Assembly, and is a member of the Board of Directors of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), but her own transition is highlighted through the two plaques inside her office. In one of them, she appears as the godmother of a university promotion and in the other, she appears as the godfather, under the name of Tomás Adrián, the same legal name she uses for bank transactions and at migration stations in airports.

The official name change request was filed by Tamara Adrián at the Supreme Justice Tribunal in 2004. She had to wait for 12 years before her case was admitted. Today, she is a member of the legislative branch and she is still waiting for a verdict.

“I know that I have to make a difference wherever I can,” she says almost like a mantra when asked if her fellow lawmakers are ready to push for a law that guarantees important changes in Venezuela's public policies and which focus on the trans community.

Denangel Meza, Joseph Soto, and Julián Alejandro Ulloa also make a difference. First, among fellow group members. They share medical guides they find online, they exchange links to videos about how to show support to family, they accompany each other during dark days, and follow protocols to take care of each other during their transition because the only certainty is that “here, having the support of a doctor is impressive. It is also very expensive,” Ulloa says.

Margaret López is a Venezuelan journalist specialized in Science and Economy. She works as an editor for the HispanoPost Media Group and collaborates with Scidev.Net in the Latin America branch. López has a certificate in Economics for Journalists by the Central University of Venezuela (UCV). Margaret López has developed her journalistic career in two large print newspapers in Venezuela: El Nacional and Últimas Noticias. In 2018, the journalist was awarded the “Arístides Bastidas” Municipal Award for her coverage of the first massive, oral Chagas disease outbreak in Caracas.

Four journalists collaborating with Tangible walked the path of trans people in Mexico, Costa Rica, Venezuela, and Argentina. These are the stories unfolded from otherness.